I think, if you're lucky enough to avoid madness, addiction, resignation, and outright suicide, you get to the point where you're tired of being miserable all the time. Tired of being miserable, tired of always looking backward, tired of reliving the same sad old stories, the same sorry failures, repeating the same apologies, grinding the same bitter old corn. What's the point of reliving all that misery; what's the point of keeping it alive? Is that what hell is in the end? Our inability to leave the prison we've made ourselves built out of regret & guilt & fear? There's no lock on the door, no bars on the windows, no prison at all for that matter. You don't have to break out of anything but your own sick penchant for a punishment of your own infliction. For crissakes. You've done your time ten times over. You can pardon yourself at any moment. Just say the word & you're free.

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

=Visitation=

(for M)

In the back of a Starbuck’s

I park

on a Sunday night

after dropping you off at your mother’s.

--it’s

one of those nights

when you take stock

of your life

in a parking lot of empty spaces

as if you’ve finally arrived

at your destination

after everyone else

has long gone…

Tonight, on the ride back,

I asked you

if you considered yourself

a happy person

and for the first time

in your 11-year-old life you paused

before answering

as if it were a trick question.

It is.

A thousand men

just like me

with the exact same story to tell

might have vanished

from this parking lot.

I wonder if you’ll come looking for me someday.

If you did, I wonder what you'd find.

If you did, I wonder what you'd find.

After a while,

I start the car

and go home.

Funny, calling anything that ever again.

Monday, February 27, 2017

=Why did Kikuo Saito Have to Die?=

I was going through some old paintings I did at the Art Students League about ten years ago and wondered what was up with Kikuo Saito. Actually, I couldn't quite recall his first name. So I googled him and learned that he'd died just a little over a year ago, February 15, 2016. He was 76 but even ten years ago, when I took two classes with him, I would have thought he was ten years younger than he would have been at the time. If someone told me he was ten years younger than that, I would have readily believed it.

He was such a sweet, mild-mannered, self-effacing, soft-spoken guy. You would hardly even knew he was in the class nevertheless that he was an art-historically important artist. I used to show up after work with earbuds planted deep in my ears listening to my MP3 player set to repeat the same song over and over and over…two hours straight of Gimme Shelter or Pretty Vacant or Werewolves of London, something loud and thought-numbing like that, pushing paint around on my canvas like some kind of autistic epileptic mental patient. I was not a happy person then, but that wasn't the only reason I was separating myself from the world—it was a way of putting myself into a trance, a way of blocking out everyone and everything else. A way of accessing a kind of self-induced, solipsistic, sacred ecstasy.

Anyway, Kikuo Saito didn't have much to say to me or the class. He barely spoke English as far as I could tell and I didn't speak period. Once in a while, he'd walk around the room and step behind you at the easel and make soft, non-directive comments. Once he told me I had a nice sense of color. That surprised me because for so long I'd been married to someone who, among my many other deficiencies, insisted that I was color blind. "Fuck you," I imagined telling my ex. "A guy who has paintings hanging at MoMa just said I have a nice sense of color. What the fuck do you know, anyway?"

Another time he asked me why I always painted figures into my paintings. Since it was an abstract painting class and he was an abstract painter it was a fair enough question. As often happens when someone asks me a question, I had no answer.

It's funny how the death of someone you hardly know—and who surely doesn't even remember you as Kikuo Saito would not remember me—can strike you, while the death of someone you supposedly do know can leave you relatively untouched. Kikuo Saito was important to me on a level that I can't logically—or even entirely consciously—access or explain, as I'm proving here.

I was stunned to learn he died—even at 76. If anyone looked like he would live on, painting well into his late 80s, early 90s, he did. I'm really sorry he died. I always liked his work a lot and the funny thing is that although I didn't/couldn't incorporate what he did into my own way of painting at the time, I did eventually see his unmistakeable influence years later, long after I stopped going to the Art Students League. At the time, though, it must have seemed as if I were ignoring him entirely. He probably wondered what the hell I was doing in his class during the five seconds or less he was thinking about me at all. But how do I know for sure? Maybe he could sense that I wanted to talk to him, that I wanted to show that I was in the process of learning from him but somehow couldn't. That there was a bridge between us yet to be built. That it wouldn't be built for a long time yet. Not until we lost sight of each other altogether. Sometimes you feel that way about a person. You don't connect with them until after they are gone. I hesitate to say "until it's too late," because it's not too late. A real connection can only happen in it's own time.

He was such a sweet, mild-mannered, self-effacing, soft-spoken guy. You would hardly even knew he was in the class nevertheless that he was an art-historically important artist. I used to show up after work with earbuds planted deep in my ears listening to my MP3 player set to repeat the same song over and over and over…two hours straight of Gimme Shelter or Pretty Vacant or Werewolves of London, something loud and thought-numbing like that, pushing paint around on my canvas like some kind of autistic epileptic mental patient. I was not a happy person then, but that wasn't the only reason I was separating myself from the world—it was a way of putting myself into a trance, a way of blocking out everyone and everything else. A way of accessing a kind of self-induced, solipsistic, sacred ecstasy.

Anyway, Kikuo Saito didn't have much to say to me or the class. He barely spoke English as far as I could tell and I didn't speak period. Once in a while, he'd walk around the room and step behind you at the easel and make soft, non-directive comments. Once he told me I had a nice sense of color. That surprised me because for so long I'd been married to someone who, among my many other deficiencies, insisted that I was color blind. "Fuck you," I imagined telling my ex. "A guy who has paintings hanging at MoMa just said I have a nice sense of color. What the fuck do you know, anyway?"

Another time he asked me why I always painted figures into my paintings. Since it was an abstract painting class and he was an abstract painter it was a fair enough question. As often happens when someone asks me a question, I had no answer.

It's funny how the death of someone you hardly know—and who surely doesn't even remember you as Kikuo Saito would not remember me—can strike you, while the death of someone you supposedly do know can leave you relatively untouched. Kikuo Saito was important to me on a level that I can't logically—or even entirely consciously—access or explain, as I'm proving here.

I was stunned to learn he died—even at 76. If anyone looked like he would live on, painting well into his late 80s, early 90s, he did. I'm really sorry he died. I always liked his work a lot and the funny thing is that although I didn't/couldn't incorporate what he did into my own way of painting at the time, I did eventually see his unmistakeable influence years later, long after I stopped going to the Art Students League. At the time, though, it must have seemed as if I were ignoring him entirely. He probably wondered what the hell I was doing in his class during the five seconds or less he was thinking about me at all. But how do I know for sure? Maybe he could sense that I wanted to talk to him, that I wanted to show that I was in the process of learning from him but somehow couldn't. That there was a bridge between us yet to be built. That it wouldn't be built for a long time yet. Not until we lost sight of each other altogether. Sometimes you feel that way about a person. You don't connect with them until after they are gone. I hesitate to say "until it's too late," because it's not too late. A real connection can only happen in it's own time.

|

| Kikuo Saito |

One of the interesting things about a blog is that you can post the most revealing details about your life, your deepest, darkest secrets for everyone to see—and no one ever sees them. You can post your PIN number, confess to a murder…it doesn't matter: your secrets are safe in broad daylight, exposed right there in public.

All you have to do is make sure they are posted two months previously.

No one ever looks backwards on a blog. The past doesn't exist on a blog…or it might as well not. It's all about what you've posted today, yesterday and, maybe, the day before. Everything four screens ago might as well be invisible. You exist only insofar as your latest post.

Tomorrow I could make this blog be about cookie baking and invite my mother to take a look. Chances are she'd never see all the pictures of me prancing around with my panties pulled down showing off my sissyclit.

On a blog every day is a new day!

Every day is a new you!

All you have to do is make sure they are posted two months previously.

No one ever looks backwards on a blog. The past doesn't exist on a blog…or it might as well not. It's all about what you've posted today, yesterday and, maybe, the day before. Everything four screens ago might as well be invisible. You exist only insofar as your latest post.

Tomorrow I could make this blog be about cookie baking and invite my mother to take a look. Chances are she'd never see all the pictures of me prancing around with my panties pulled down showing off my sissyclit.

On a blog every day is a new day!

Every day is a new you!

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Saturday, February 25, 2017

=burn diary=

|

| Baptized by Sharks With Cocklight |

Well, I can't entirely explain this one. But I'll take a provisional stab at it. As a good little Catholic child, it wasn't Jesus who I admired most of all; it wasn't Christ who seemed most worthy of emulation—after all, he was the star of the show, he got the spotlight and the accolades. It's not as hard to sacrifice yourself, I figured, if you got the top billing. Not hard to let yourself be crucified if you knew deep-down you were actually God Himself and your death was basically an act in a passion play.

Instead, it was the all-too-human John the Baptist who seemed to me the epitome of modesty and altruism. He could have claimed to be the top dog but deferred to Jesus. He admitted he was nothing more than a second-banana, a faithful lieutenant, the emcee introducing the Greatest Show on Earth. "Heeeere's JESUS!" he said, working the audience into a frenzy, and then stepping off-stage into the shadows.

At some point, I saw Leonardo's incredibly sexy painting of John the Baptist and I immediately and instinctively felt that I wasn't looking at any ordinary man—rather, I was certain that Leonardo had coded a visual secret in plain sight into this painting: John the Baptist was a transgendered person. John as imagined by Leonard was a boy-girl, just like me. My identification with him/her was complete.

It seemed clear to me that John adored Jesus the way a woman loves a man—because he was, essentially, a woman. Then came the part where Salome tries to seduce him with her Dance of the Seven Veils. John remains unseduced. Why? Because, as a heterosexual transwoman, he cannot be seduced by Salome. S/he is a seductress him/herself. S/he knows all the tricks. What's more, s/he wants to play that role; it turns her/him on to dance for men, just as it does Salome. They are one of a kind. So John loses his head…i.e., he's castrated.

I suspect that "explains" the background of a lot of what is going on in Baptized by Sharks With Cocklight.

Thursday, February 23, 2017

=burn diary=

|

| I Make Mommy & Daddy Happy |

My parents liked to stress how grateful they were that unlike other kids my age I never demanded toys or candy or threw a tantrum if I didn't get my way. It never seemed to occur to them that my behavior had nothing to do with being a well-behaved child or that it was a result of their excellent parenting skills—but that it was simply because I was scared to death to express any desires of my own. Any instinct to vocalize my preferences had been thoroughly squashed out of me from the earliest age. As a result, I took whatever I was given and acted as if I were happy to have it. I also think I instinctively understood that my parents were unable to give me what I needed so there was no sense even asking. It would only frustrate and enrage them.

Neither of my parents seemed to have any strong affinity for spiritual matters but I was a naturally very religious child. I was very taken with the image of the crucified Jesus. From very early on, my nascent sexuality was joined to the notion of self-sacrifice and I began to eroticize various versions of sadomasochistic immolation. It seemed obvious to me that Christ dying on the cross was a metaphor for what I was experiencing when I had my childhood orgasms. That is partly what is going on in this picture. I am sacrificing myself to my parent's unhappiness and eroticizing the pain in order to better bear it. Unfortunately, it is a useless sacrifice. Nothing I can do, not even letting myself be crucified for their sake, can make them happy.

Significantly, it is my father who has nailed me to the red cross, which might also be the "forbidden bed" of incest. Perhaps he is trying to overcome his illicit desires even as he relieves them via masturbation. He is punishing me for leading him into temptation but also for his perception, probably accurate, that my mother prefers my company over his. But if she prefers my company to his it is only because I pose no sexual threat to her, that I make no sexual demands. Our perceived bond is superficial. What my father doesn't realize is that my mother doesn't nourish me either, not in the way a child needs to be nourished by its mother. In this picture, my mother walks away from the cross without so much as a backward glance at the suffering I offer up as a sacrifice. Perhaps she is disgusted at the evidence that my suffering has aroused me sexually. In this respect, I am as "bad" as my father. She has covered up her breasts because she has never wanted to be a woman. What she wants is to remain a little girl. She is looking for the sexless protection of a good daddy of her own, which she has always longed for and never had.

We are three people who cannot save each other. This is a crucifixion with no resurrection, in which no one and nothing is redeemed.

Although the violence and the crude ugliness of this image may belie my claim, the fact is that I have forgiven my parents their transgressions. They truly did not know what they were doing. They were, in their turn, victims also. I understand this now. But, as Alice Miller has pointed out, I've discovered that forgiving isn't forgetting; more importantly, forgiving isn't healing. You can forgive someone for a grievous injury, for chopping off your hand, for instance, but that doesn't regrow your hand. The damage done isn't undone. As Solomon says in Ecclesiastes, the bent branch can not be unbent. The body remembers the injuries done it—the pain, the fear, the stunted desires—all live on inside you. These cannot be "understood away." No amount of intellectualization can melt away the scars.

Scars don't heal. But they are evidence that some sort of healing has taken place. They are what's left after something's been irretrievably lost. You can either cover them up or wear them openly, even defiantly. Scars are the medals life hands you in honor of your survival. Everyone has them. Someday—a day close at hand, I hope—I may even come to the point where I can wear mine proudly. Perhaps—is it too much to expect?—with a kind of gratitude. <—(Oh for crissakes, come off it. What noble sounding sentimental rubbish. I let my own rhetoric get away from me again. I'm a deeply scarred, disfigured, hideously crippled person & that's that. Nothing to be proud of or grateful for. I survived to this point mainly by dumb luck and sheer terror of the alternative. It is really of little consequence whether I continue to survive or not so long as either way I keep the negative impact on others as minimal as possible. That's the best I can do. As Anne Sexton said, "Live or die, but don't poison everything. " That about sums up my position on the matter. )

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

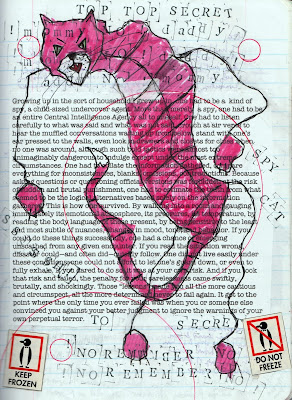

=100 Daddies=

The first man I ever called my father won me at a card game

when I was three years old, lost me at seven, won me back at eight, lost me

again. In between, I’ve lost count of the number of men among whom I’ve been

passed.

To keep things simple I called them all “daddy.”

Who my real father was is a mystery to me. I have never

known a time when I was a virgin. I guess you could find in these facts an

explanation for my troubles with men.

I killed my first man the month before I turned eleven. He

kidnapped me outside a convenience store in Camden, New Jersey. I let him rape me in the back of a van.

All in all, it wasn’t as bad as Camden.

I was so passive, so perfectly compliant, that he felt

comfortable enough after he came inside me to fall sound asleep. It is then

that I picked up the tire iron I found lying on the floor under the cot and

beat his brains out. It was then that I learned a most valuable lesson: men

often mistake passivity for weakness.

As I sat there regarding my handiwork, I was suddenly seized

with an irresistible, inexplicable urge. I gnawed the bastard’s cock and balls

off. I did it purely by instinct. I had no idea what I was doing or why.

I munched my way through all that flesh and hair and

cartilage. It was a bitter, foul-tasting experience, a lot like my life up to

that point, but somehow more satisfying.

I screwed up my face with distaste, but I got through it as

I’d gotten through so much up to then: somehow.

The second man I murdered I did away with in a fleabag motel

somewhere between Iowa and Kansas. I never was very good at geography.

The circumstances of our meeting were a little more

ambiguous than those of my first victim. I’ll spare you the details. It

followed the general pattern. “Come here, little girl. I’ve got something for

you.” Hand over mouth and nose, pointless struggle, tied, tossed in the trunk,

etc.

Tires squealing.

Bumpy ride.

The ending was much the same.

I cut his throat as he lie snoring and farting his way

through a drunken stupor. He’d been careless with the electrical cord he’d used

to bind my wrists and ankles. Big mistake.

As the last of his blood spurted out, I grabbed his cock

before it could go completely flaccid. I pumped him up real hard. I stared

right into his terrified eyes and bared my teeth. I ducked my head over his

lap. This time I didn’t hesitate. No tentative lick.

I dug right in.

Yum.

The third one…well here is where my memory starts to get a

little hazy.

In my experience, you really remember only the first couple.

All the sights, the sounds, the stenches. The reassuring heft of the tire iron

in your hand. The wet and satisfying squelch of that initial meaty blow. The

effortless way a blade melts into flesh. The alarmingly beautiful pattern of

blood as it sprays across a mildewed wall.

And most memorable of all, the first sweet taste of candied

man-flesh. Because that’s how I’d come to think of a man’s death-stiffened pole.

As a smooth, shiny candy. A sweet treat. A Valentine from me—to me.

Just like pink chocolate!

A guilty pleasure except I don’t feel any guilt.

After sixty, seventy, eighty, who’s counting? You get jaded,

the details start to blur, it’s like being on a merry-go-round. Names, faces,

the order of events, it all starts to bleed together. The truth is that it all

resolves itself into one archetypal Ur-story of sex, murder and mayhem.

Well, that’s okay. Order and sense have nothing to do with

it. I don’t plan on making a confession. That’s not my intention. At some point

I slipped up, got cocky (pun intended), and found myself underestimating my

prey as they had once underestimated me, the stupid pricks. It happens.

I got caught, muzzled, convicted, albeit, the judge

conceded, with extenuating circumstances. I’d lived a tough life. I was never

shown the proper love. I was more sinned against than sinning.

My crusading lesbo-feminist lawyer argued on my behalf with

maternal ferocity and righteous indignation; no one ever defended me from the

cold cruel world like she did, not even my actual mother, whoever she might

have been. She convinced the jury of nine men and three carefully chosen closet

dykes that I was more victim than victimizer.

But most of all, what saved me from hard time was simply

this: I was too pretty for the penitentiary.

Someone took an interest in me. He—naturally it was a

“he”—rescued me from the prosaic prison in which they would have interred me

for a minimum of five years of tedious counseling and ultimately futile

rehabilitation. He brought me instead to his mansion on a secluded ranch in the

mountains surrounding a pitiless stretch of Nevada desert. I have no idea how

he accomplished this feat of legal hanky-panky, but I suspect it involved

considerable sums of money and a crooked politician or two.

My new captor wasn’t interested in my rehabilitation. He

wasn’t interested in justice. He wasn’t even interested in the truth, not the

way the police were interested in the truth, for instance, or the

court-appointed psychiatric worker, or my legal aid attorney, or any of the

well-meaning but clueless social workers from the Division of Youth and Family

Services.

No, my captor simply wanted to hear me sing. He knew that song has it’s own truth, a truth that can’t

handcuffed to morality or even facts, because the truth cannot be held

prisoner, not even to things like right and wrong; the truth is Houdini-like,

it always escapes. The song, like violence, belongs to a higher order of

things, where truth and beauty merge...and emerge into something that

transcends this world.

Like an angel.

That’s what he called me. Daddy’s Little Angel.

And that’s what I did: I sang. I sang inside the pretty white cage he kept me confined

inside day and night. I sang of all the glorious, terrible, ecstatically bloody

things I’d done in my short incredibly violent life up to that point.

My captor was anonymous to me. I never saw his face. He kept

it carefully concealed behind a mask whenever I was to perform for him. He was

a careful man, not at all foolish, like all of the rash and careless men I’d

known up to that point.

When he fed me the candied sweets I craved from his own

hand, he always wore a thick leather glove through which he knew my teeth

couldn’t penetrate. Not even once did he fail to put on this glove when he

reached between the bars of my cage.

Believe me, I was waiting for him to make a mistake, for him

to trust me. I was waiting for him to grow careless just that one time like all

the other men I’d ever known. One

slip up and I’d have snapped, taken his hand right off at the wrist if I could,

chomped my way through the salty veins and cabled tendons.

He never slipped up though, not even when he was tired from

the labors of his long days away from his desert mansion getaway, not even when

he was intoxicated, and, most impressively, not even when his cock was standing

straight up against his paunchy, furry belly, poking up to play.

At those times he had me turn around, bend over and present

my bottom. And he took me just like that, from between the bars of my ornate

cage.

He never forgot—even at the moment of his most explosive,

thought-shattering orgasm—what I was, how lethal I could be, and because of

that ever-vigilant watchfulness I understood that he was the first man who ever

truly respected me.

And it was for this respect that he had for me that I in

turn felt for him something equally special. Something that I never felt for

any other man. Something that I imagine is akin to what other people must mean

when they talk about “love.”

I “loved” my captor, my latest daddy. Because if he so much

as let his guard down for an instant, I’d kill him without so much as a second

thought.

But he never did.

He never, not once, disrespected me.

I don’t know how much time passed like this. Years, maybe.

If I’d gone to a regular prison, I would probably have earned my release by

now; provided, that is, I didn’t kill one of the guards, an all-too real

possibility given the prevalence of sexual harassment in the prison-system.

Eventually I noticed that my captor was coming to see me

less and less. Perhaps he’d gotten tired of me?

When he did come, he looked drawn and rubbery-faced. He

appeared to be dramatically losing weight, his skin taut and yellowed. He had

trouble lowering and raising himself from the chair he pulled up in front of my

cage. He moved cautiously as if in anticipation of pain. He winced often when

it came.

Eventually, he confided in me. He had a complicated cancer.

It was seated in his liver like a nest of spiders and was eating away the rest of

his gut. Recently, his doctors found new colonies nested in his lungs and

brain. He laughed. He could see I didn’t give a damn about his problems. He

could see the question plain on my face. My one and only concern. What was

going to become of me?

The answer came some months later, when all the various

experimental treatments only the rich can afford had failed, when the hope of a

spontaneous remission was less than the likelihood of a miracle.

He rode into the room one afternoon looking like a skeleton

in an electric wheelchair. In his bony fingers, he held up a key. He inserted

it in the lock and left it there.

He said, “Free yourself.”

Then he said what we both knew already. “I am your Daddy.

Your real Daddy.”

He stood back and waited.

I reached through the bars of my pretty cage, the only real

home I’d ever known, and turned the key. The lock snapped open.

I strode out, free as a bird, naked as the day I was born.

I knew what he wanted.

He wanted me to kill him and eat him. He was so certain that

I’d jump at the chance he didn’t take any precautions. His shriveled up,

impotent thing sat in his lap like a dead baby bird in its nest of ashes. But I

didn’t bite. Instead I walked right passed him and out the door. I let the spiders

in his gut finish him off.

The son-of-a-bitch deserved nothing better.

I crossed the desert, killing only as the need arose.

Strangely I found that I no longer derived any pleasure from it. Or not much.

The flesh of my victims no longer tasted like pink chocolate to me anymore. I

guess I lost the taste for it, if not the aptitude.

I’d gone straight.

Well, as straight as a girl like me can go.

I made it to Las Vegas. I managed to hustle a job as a

housekeeper. I met a high roller in one of the casinos who regularly dropped

small fortunes at the roulette wheel just to pass the time.

“Who is that man?” I asked one of the guys who worked casino

security.

“He’s an oil tycoon” was the answer.

He wears a ridiculous ten gallon hat and has steer antlers

fixed to the front of his Caddy. We were married eight days after we met in his

unmade bed. I had taken it upon myself to augment hotel policy for high-rollers,

going to his room to comp him a complimentary wakeup blowjob along with some

extra bath towels.

Now I stand on the balcony and survey a stretch of Texas that extends all the way to the

horizon—and a good deal beyond that, too. You’d need a telescope to see it all.

The land, the oil rights, even the senators …one day it will

all be mine.

His legitimate children, all well into their middle-age,

hate me, of course. But there’s nothing they can do about it. They’ll mount

legal challenges that will last years. I’ve got a great attorney—the crusading

lesbo-feminist, now my lover. Meanwhile, I’m already diversifying investments,

moving mountains of money to the financial equivalent of Pluto. Sherlock Holmes

wouldn’t be able to track it down.

He’s on the far side of eighty. And when I step on his

accelerator, I can hear his heart stuttering to make it to the finish line.

It’s just a matter of time.

Just to piss my new brothers and sisters off, I call him

“daddy.”

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

=burn diary=

|

| Daddy With A Gun |

Monday, February 20, 2017

=burn diary=

|

| Hearing Mommy & Daddy Fighting on the Other Side of the Wall |

Sunday, February 19, 2017

=burn diary=

|

| The Long Walk Home from School |

At the far right, my father in his skeleton suit, never far from my thoughts.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Monday, February 13, 2017

Sunday, February 12, 2017

=Oaf the Plant in Second Gear=

Tell me

but don’t say it

the cartoon years

the Green Giant tears

the laugh track

flying by like miles

passed the window

smoke stacks

haystacks

carpet tacks under the tongue

cows under the moon

roadside buffoon

sign in his hands

you missed the second coming

but you’re just in time for the second going

did you see that right

second sight

please help

on the flipside

in the parentheses of his filthy claws

please help

but did i

did you

help who

after all those solo systems

you wandered through

after all those solo systems

you wandered through

Topeka 24 miles ahead

Indian head

Wonder bread

hard-ons in empty rooms

did you ever stop

stop to consider

after all those miles

candy smiles

what’s making all

those strange beds strange

in all those empty rooms

in all those empty rooms

is you

Thursday, February 9, 2017

|

| (Tomorrow this painting will be different & the day after that & the day after that…so will you.) |

Art is never finished, only abandoned, said Da Vinci, which to me, indicates that the epitome of a living work of art is a graffiti tagged wall, which is never "finished" but subject to perpetual and endless revision.

It was Sartre who reflected that no man could know the ultimate meaning of his own life because that was something that could only be known after his death, when the life was complete, leaving the problem of synthesis and interpretation to others. Or maybe it was Bataille who said that. Bataille, who left his work consciously "unfinished." Or maybe it was Sartre reflecting on the life and work of Bataille who said it.

Or maybe.

Or maybe.

Or maybe.

Just so, my recent canvases reflect the idea that no painting, like no life, is over until it's over. It's all about process. One day it's pretty bad, the next day it's even worse; the day after, a slight improvement, followed by a regression. At some point, maybe it's almost beautiful, but the next day, christ, what happened...it's all fucked-up again. Everything is in a constant state of flux. It's like looking out the window at the weather…or out the window of a bus traveling across the country…the scenery is always different.

The canvas—or wall—or train-car siding—is like a diary being written & overwritten. It would be great to have a museum hung entirely with canvases which visitors were encouraged to mark up as they passed through (what better "picture" of humanity?)…or if one's house were hung with such canvases, where all the people living there and even the guests left a record of their visit on the walls as they leave their record upon you.

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

=Geisha in the City of Death=

“One would like to arrange the book to resemble a house that

would open easily to visitors; yet as soon as they went into it, they would not

only have to get lost there, they would be caught in a treacherous trap; once

there they would cease to be what they had been, they would die.”

–Maurice

Blanchot

“…or he’ll select a favorite ingénue and assault her with a

thick impasto of pirates, sailors, bandits, gypsies, mummies, Nazis, vampires,

Martians, and college boys, until the terrified expressions on their respective

faces pale to a kind of blurred, mystical affirmation of the universe. Which,

not unexpectedly, looks a lot like stupidity.”

–Robert Coover

1. You are

dead.

Of course, it takes a long time to believe that. You've died

so many times by now. You say, “I am dead.” But how can you say “I am dead” unless

you’re still alive?

That conundrum stumps you for a time.

Eventually it dawns on you that it can also work in reverse.

Only if you're dead can you be murdered as many times as you have. Perhaps the

dead, too, can fool themselves. Perhaps they, too, can say, “I am alive” and

mean it only as a figure of speech.

Going round and round like this…after a while you just stop thinking about it at all. Alive or dead, it stops making any difference.

Neena is sitting in her room as the first stars begin to

appear on the monitor behind her. The monitor displays a purple sky of

impossible depth and unspeakable beauty. She's already dressed for the

occasion: the white fishnet stockings and the white micro miniskirt, the

five-inch silver platform sandals, and the elegant gloves, white, satin,

elbow-length, with the forty-nine tiny pearl buttons running up to each

alabaster elbow.

She's wearing a corset comprised of the ribcage of a

murdered teenager, which has been laced tightly enough to reduce her breaths to

tiny sips, like a deep-sea diver out of her depth, hopelessly conserving a

limited supply of oxygen. Her breasts, enhanced by surgery and indelible inks,

are cupped inside this cruel corset. The bra cups are formed from the skeletal

hands of the two children she shall never bear.

Her left nipple has been pierced. That is the custom here. But

the charm which dangles there is unidentifiable--a Martian hieroglyphic?

Earlier, her geisha-corpse makeup was applied by her

Japanese transsexual maid. Oh yes, they have those here, too.

Her hands are lying uselessly in her lap as she faces the

upcoming endless night with no personal expression whatsoever.

"Are

you ready?"

"No,"

she whispers.

"Then

come."

Someone,

unseen, in the darkest corner of the room, has been masturbating. Finally,

after much effort, he or she reaches a shuddering climax that makes the very

atmosphere twitch.

Neena takes the proffered hand of the undertaker, who is

dressed, predictably, in formal black. On his face, he wears a mask of black

silk, as if he were afraid to

breathe the molecules of death floating in the air of this place. His eyes are

entirely abstract. He will never fuck Neena, never, not even after the passage

of another thousand years.

Neena rises from her chair, unsteadily, as if from past abuses such as

those not even fantasy can quickly and completely heal. She moves, still

dreaming, towards a door that seems always to be opening into some new

nightmare.

She tells

herself that she will remember this time, just this once, but she knows that

she has already completely forgotten everything that is about to happen.

These marks of ardor on the soft and surrendering flesh serve as an ever-present reminder to the regular inhabitants (aka prisoners, dreamers, etc.) of this section of the mansion. A reminder of what, though, is a variable sum.

2.

Time does not exist here.

Time does not exist here.

There are no clocks or watches anywhere. But it’s unclear whether this is by edict or simply because such instruments are irrelevant in such a place. Perhaps they simply don’t operate here.

How do you measure eternity?

No one is born and no one dies in this place. No one ages, or, if they do, it happens at such an incremental level that you cannot see it actually happening. Imagine seeing only one frame of a bullet captured on film in mid-flight towards the innocent lover it is aimed to murder.

There is no coming here and no leaving here, never a time that one wasn't here, and never a time when one won't be here again.

It's an immortality, of sorts, Neena thinks, whenever she feels the life draining from her cold toes for the millionth time and hears the distant, polite, yet ever-so-slightly bored applause of jeweled hands that have never touched a thing that had its origins on planet Earth.

In the hallway of this subterranean complex Neena presses herself against the wet wall to let a gurney pass. Upon it, a creature lies like a broken butterfly.

It is not uncommon to see victims being brought back to their rooms at any hour of the day or night, or, wheeled, full-speed, down to what is presumably the emergency surgery for unnecessary and futile procedures. The attendant pushing this particular gurney is almost invisible, a mere outline of an attendant. Neena has to look closely to even see him, or her--it’s usually impossible to tell their sex--otherwise the gurney would seem to be propelling itself.

Maybe it is.

The stylized faces of the attendants are designed to approximate the same dreamily expressionless mask of implacable indifference that might be seen on department store mannequins. Perhaps it is even more accurate to say that their expressions mimic what might be the result of an autistic’s rendering of moon-people, drawn left-handed, with eyes closed, in a hypnotic trance.

Neena, dazed and dizzy, stands confused at an intersection of featureless corridors.

She tells herself not to look at the victim on the gurney. But she looks, anyway. Who wouldn’t?

They have purposely denied the girl the dignity of a sheet to cover her abused remains. The terrible cruelties inflicted on her body are on display for the sole purpose of enflaming the passions of whatever guests might be strolling the halls.

These marks of ardor on the soft and surrendering flesh serve as an ever-present reminder to the regular inhabitants (aka prisoners, dreamers, etc.) of this section of the mansion. A reminder of what, though, is a variable sum.

Back to the blonde girl on the gurney (before she is wheeled away forever and we think of her no more): she is naked, as mentioned (I think) except for a pair of red, high-heeled ankle boots. She has been cored through the middle, where her navel had been once, by what looks to have been some kind of huge, minutely machined screw-bit. Whatever the actual cause of death, that unnamable engine of destruction has left an absence at the center of her being that makes of her corpse the perfect comic representation of a woman who, for one reason or another, could never satisfy her need to be filled.

There is a look of utter horror on the blood-speckled face that has accentuates, in fact, amplifies, a delicate beauty which puts Neena in mind of a cross between the white garters she is wearing and a slice of French vanilla cake.

“Absurd,” Neena murmurs and licks her lips, unconsciously.

They are taking the poor girl off to be repaired (ha-ha), or altered, or fucked by one of the necrophiles who pay handsomely for the privilege of abusing, with absolute impunity and no-questions-asked, a pretty, blameless, and terribly disfigured young corpse. They come to the topside gates of the compound above the necropolis in limousines and private jets, in helicopters, and aboard intercontinental yachts. At least such is the rumor that sifts down to this place deep inside the earth, which could be Hell, if Hell existed, but is not.

It makes no difference to Neena.

She has her own fate to fulfill, and she must hurry to her appointment along a corridor that leads even further, even deeper, passed a “no exit” sign, along a one-way corridor into the very bowels of the subterranean sex mansion.

3.

3.

Tonight Neena is to be poisoned at dinner.

It’s no secret; it’s on the printed programme, after all. She has suffered this fate before, perhaps, or one nearly identical; she can’t remember exactly. She has lived so many lives, died so many deaths. It’s really impossible, after a while, to distinguish one from the other, and who would want to?

She enters the formal dining room, which, on other nights, could be a prison cafeteria or Beowulfian mead hall, without introduction or fanfare. A butler, dressed formally, motions her towards her place at table, where at least eighteen other exquisitely garbed guests sit chatting amiably about nothing much at all as they await the imminent arrival of the first course.

Neena is inadequately and inappropriately dressed for the affair. This is immediately apparent—and, of course, premeditated. Neena blushes. She sits as the chair is slid beneath her by an officious if utterly indifferent waiter. She is relieved that no one so much as glances in her direction to acknowledge her arrival. You can always depend, Neena thought appreciatively, on the cultured to behave with complete sangfroid, even in the most horrendously awkward situations. To see nothing requires a grace more delicate than charity.

Self-consciously, Neena lays her left hand near the snowy napkin upon which rests more silverware than seems necessary, or even possible. Are they performing experimental surgery at table tonight, or what? She notes a pleasing correlation between the white delicacy of her fingers and the exquisite thinness of the china, which appears to be made of bone sanded and buffed to an excruciating near-transparency that is shine alone.

She finds herself questioning, in spite of herself, if maybe she has somehow come to the wrong place, after all. Her alienation from the others at the table is so total. She begins to think it possible that she misread the agenda of tonight’s performances. Perhaps she was scheduled to be hanged tonight, instead?

She knows, intellectually, that her fears, in this one area, at least, are groundless. Although a love for random violence animates the mansion, one can have faith in the unerring bureaucracy that nonetheless prevails. A monstrous impersonality that is all-inclusive, even of the principles of opportunism, chance, chaos, and quantum mechanics.

Nothing here ever happens by accident.

If Neena has any doubts at all, her skepticism is only one pole of a continually oscillating psychic state that holds her in place, torn apart in constant agony, a crucifixion between insecurity and childlike trust.

The initial toast is poured into tall, exquisitely hand-blown flutes (containing the breath of mothers dying in childbirth, so they say).

Neena lifts her glass, in perfect unison, along with the others, to her black rosebud of a mouth. She understands not a single word offered in benediction by the toastmaster, spoken as it is in a tongue that is completely alien to her. It sounds liturgical. No one touches her glass, but the others, touch theirs together. That sets the glasses all to singing like a flock of small, bright, migratory birds shivering in dead trees.

They drink to seal the toast, grinning.

Neena brings the flute to her lips and kisses the taste of pale light an autumn afternoon.

In a flash she sees: a rocking chair before the window and, slumped there, a woman of indeterminate age, She has apparently overdosed on tranquilizers because she could not bear to grow even a single day older.

Looking closer: Neena notices that from the cold blue fingertips of the dead woman’s hand a flute has fallen, a flute exactly of the kind (if not the very one) from which Neena sips at this moment.

Neena wonders, albeit briefly, if upon taking that one sip, she has already been fatally poisoned.

The soup course is first.

Neena lifts to her blackberry lips a spoon so impossibly light it may or may not be obeying the laws of gravity. The pale broth has an elusive flavor, as if the game used to season it were still fleeing.

Bon appetite!

Several equally exquisite intermediary courses follow (to be concise about it), some or even all of them quite probably poisoned. Neena knows that each time she lifts her fork it could be the last. Any bite, either by itself, in tandem, or, more likely, cumulatively, could deliver the lethal dose. Such a flair for deadly flavoring was the hallmark of the gourmet poisoner today. The sense of expectation raised among the other diners is atrociously, indescribably yummy.

The conversation around Neena is lively. At the moment there is a discussion underway about the most recent political developments in the capital. But the figures of whom they are speaking are entirely unknown to Neena, although, obviously, they are personages of such prominence one could not possibly be living in these times and be unfamiliar with their names. Apparently, some of them are even seated at the table!

It all means nothing to her.

Even stranger, despite the heated nature of the discussion, the great depth and complexity with which they discuss the burning issues of the day, Neena can’t help but note that no one seems to be taking any of it seriously at all. It’s as if the discussion were only an elaborate and intense kind of adult parlor game, like bridge or canasta, the rules and goal of which Neena just cannot parse out.

A woman eventually turns from the conversation to gaze, if only briefly, at Neena, her plucked eyebrows a semaphore for permanent amusement. Her stylized, tiger-striped metallic eyes look Neena up and down, pass a mute but deafening judgment of faux-haughty disdain, and then she turns abruptly back to the red-bearded hunter seated on her right. Laughing, she says something about the brutal last days of an emperor of an outlaw corporation to whom she was apparently once married.

The burning on Neena’s lips grows steadily more intense. Up to now, she’s been telling herself it could be the result of too much cayenne pepper in the eighth course. But the burning has intensified to a truly ominous degree. It feels like an army of red ants have set up camp in her mouth and lit a thousand campfires on her tongue.

Hoping to appear nonchalant, Neena stays her hand on its inevitable trek to the water glass for as long as she can stand it. Then she finds herself gulping down the contents of the glass with short convulsive swallows, in spite of her efforts at an indifferent discretion. The water, she knows all too well, is certainly poisoned (that’s the failsafe, after all)—it tastes of peppermint echoes.

For the moment, everything reminds her of the backyard pool of her childhood, her handsome, sadistic father, his underwater seductions, and a crystal skein of semen, blood, and carbon dioxide bubbles twisting toward the surface…

Neena foresaw the outcome of her impulsive attempt to quench her thirst. Yet she is still surprised at the Technicolor blossoming of pain, a time-lapse Vermont fall foliage of breathtaking agony, that spreads across her chest and along the inside of her throat, an incandescent glow like an overexposure to some sort of interior radiation.

One of the servers, the one whose duty is circumscribed by this sole function, refills Neena’s glass silently and automatically; indeed, this server--and, incidentally, not this server only--may, in fact, be an automaton.

Meanwhile, the party goes on.

A woman chosen for her strong familial resemblance to Neena, leans forward and asks, “Can you imagine an aunt doing this to you? Or perhaps it could be a dear friend with unrequited or betrayed lesbian feelings?” The woman slow-winked a long cat-eye. “Maybe it can be both, yes?”

Neena gasps for air by way of answer.

The main course, Neena suddenly realizes, has already arrived (perhaps, she passed out in the interim between the various salad and cheese plates?), and, from the state of what remains on the plates around the table, that everyone has been eating for quite some time. She presses a fork, which suddenly appears in her hand and all-but guides her motion, into a thick white meat of what seems almost certainly to be some unknown variety of deep-sea fish, the kind that must be caught in hadal depths, that lives under pressures so intense it has evolved in an exploded state, that is, with all its vital organs on the outside of its body.

Neena hesitates, spears, and then lifts to her mouth the grey mottled jelly of fish flesh.

Yuck!

Neena chews slowly, reluctantly, meditatively, savoring the horror, an unnamable sauce, even as she checks the closing of her throat, the instinct to gag, to puke out this coprophagic feast of filth. Yet in spite of her revulsion she manages, miraculously, to keep it down.

Bite after bite, each time she swallows a masticated bit of the spotted poisoned goop.

There is talk about a Brechler symphony, about a church massacre, about someone’s “impossibly” dyed hair. The Times is mentioned (but which Times is unclear), a movie about the Lasky incident, endoscopic surgery. Kroner, juniper, Los Angeles, unnecessary casualties, epidemic bread, Kroner again, snow, skin grafts, nanobiology, and elective mental breakdown—fragments of these conversation snag her attention like barbed wire the prison jumper of an escapee.

The first of the more severe stomach cramps abruptly folds her in half. It takes all of her will-power and concentration to delicately place her fork down on the napkin and even so she is certain that in spite of everything she has laid it on the wrong side of one of her six salad knives (one is missing). There are severe penalties for such a breech of etiquette.

The second appalling pain causes her to disturb her wine glass with a weird and hermetic gesture of her right hand, which has suddenly, and ominously, become, as it were, withered and incapacitated.

“Always,” she hears someone say, but nothing follows.

It is the asexual fashion designer with the false jaw who pronounces this isolated mountain-peak of a word, seated as he is across the table and one chair to the right.

Sometime later, someone else adds, “the color of orange at 4p.m. in Andujar.”

4.

4.

When Neena opens her eyes again, she cannot see out of the right one. She is gasping and she has begun to foam at the mouth. No one seems unduly alarmed.

“One must mix carefully to get the full spectrum of desired effects and still you must make sacrifices [inaudible passage]. A good deal of this has taken place over a period of several days duration.”

An older woman--Neena has seen her often before, but where, under what circumstances she can’t say--interrupts her own conversation (about insect-derived poisons) to turn to Neena and ask, solicitously, “Are you quite alright, my dear? You’re looking rather peeked. You might want to redraw your lipstick.”

Neena is chilled from scalp to toes with a transparent sheen of sick sweat and she is suffering from an uncontrollable tremor, but she actually manages, to everyone’s surprised delight, to take four spoonfuls of the chief desert course, a creamy crème brulee made of whale eyes.

She tries to smile, absently, albeit knowingly, when someone on her left pretends to ask her opinion of that new athletic satire causing such a stir among the Estraud faction. She struggles for form an intelligent answer but realizes that her interlocutor has only used the question as an excuse to examine her more closely. He is checking the second hand of his watch for the eagerly anticipated beginnings of morbid cyanosis.

Neena feels her heart stagger into a ventricular fibrillation which in turn triggers her adrenals like a starter’s pistol initiating her all-out flight response. But flight--to where? She is far too disoriented and polite to do much more than vaguely excuse herself and half-rise from her place at table with a gesture of elegant resignation (a gesture later much discussed, admired, and copied), which she makes with her as yet only partially paralyzed left hand.

The floor comes up quickly, quicker than possible! (how is that possible?). When she revives to a state of semi-consciousness, she is lying on her side and convulsively vomiting as if trying to turn herself inside out. She vomits as if giving birth, by mouth, in a burning flood of blood and mucous, to Death itself.

One of the ridiculously impractical platform fetish sandals she’s been wearing has come off. Her skirt is hiked up over her right hipbone, revealing the starry-spangled g-string that bisects the smooth angel-dusted globes of her perfect ass. She can feel the garters have unsnapped on the back of her right thigh and the fishnet stocking adorning that leg has worked itself a few inches down the back of her very white flesh. The image would be aesthetically complete, she believes, if one of her breasts were simultaneously exposed, but the only way that will happen now is if someone reaches down to help slip a soft tit out of its lacy cup in order to expose her in this lovely fashion.

She is aware of all these details, and several more besides, and aware of it all in the ever diminishing intervals between each hideously violent constriction of her entire gastrointestinal system.

“Designer poisons, I’m afraid, are an absolute necessity,” Neena hears someone say. “You simply can not get such a rainbow plethora of reactions from any combination of natural poisons alone. Believe me, I’ve spent the better part of a lifetime trying. Not the worst way to spend the better part of a lifetime either, I might add.”

“Indeed,” concurs a chuckling man, who has stooped down to examine Neena more closely through a monocle. He slips her tit out. “Nature is so limited.”

“Magnificent,” another voice says. “She has turned quite an unearthly tone of blue.”

“Death occurs on a variety of fronts,” still another voice points out, droning somewhat pedantically. “There is, of course, the collapse of all major organ systems: respiratory and circulatory, for starters. The nervous system goes haywire before it shorts out completely. It is a catastrophic assault on the entire body from within. Quite painful—and yet remarkably…”

Either the sentence isn’t finished—or Neena cannot hear it. Instead the next thing Neena hears is this:

“I note, with extreme satisfaction, the issue of blood from her anus…”

The voice belongs to a female, it is both enthusiastic and insinuating.

“Yes, major hemorrhaging from there as well. She’s quite ruined, I’m delighted to say. A biohazard. Dangerous to even touch; I wouldn’t recommend trying.”

Neena hears nothing any more. From this point on, she’s stone-deaf. Her jaws are locked open and her eyes, tear-fringed lids a- flutter, have rolled back. She is crying, quite literally, tears of blood. Her long delicate fingers are curled into tight babyish fists, and her nails puncture her palms, a pseudo-stigmata, in wounds that form an alchemical hieroglyphic.

But back to Neena’s point of view (while she still has one): her rapidly diminishing boundaries of concern have already left her with very little point of view at all, just a rapidly dimming pinprick of awareness, through which she gazes as if at an eclipse. In this case the eclipse of her own life.

A team of men in white protective clothing, complete with masks, now surround her. They wield disinfecting machinery and wear reptilian breathing devices.

Neena dies without so much as a shudder, her body already locked in a spasm of such rigidity it is impossible to compare it to anything.

She is more than dead, she is hyper-dead.

She is beyond even necrophiliac desire, dangerous and untouchable--a thing beyond taboo.

She feels nothing, as usual, except what might be felt from the post-conscious knowledge that no one is interested in her any longer. The wreckage of her liquefying corpse has been lifted, deposited, and is now being wheeled unceremoniously from the dining room in a grey cart marked on all sides with the bright yellow warnings signs for toxic waste.

She will be dumped into the chopping cold waters off the Jersey Shore sometime later that night. Her processed remains will be pumped through the bilge system of an unmarked tanker along with other illegally dumped chemical and radioactive byproducts from various secret, underground medical and technical weapon facilities along the east coast.

Meanwhile, the guests in the dining room are enjoying mints and aphrodisiacal rattlesnake-blood aperitifs.

5.

"This is my first time," the girl says. She is lying, naked, on her back, across a red oriental-style footstool, fingering herself to an orgasm that never comes.

"This is my first time," the girl says. She is lying, naked, on her back, across a red oriental-style footstool, fingering herself to an orgasm that never comes.

Neena looks at her blankly, as one's eyes might fall on an empty white ceramic cup, the heavy, utilitarian type you’d find in a diner. She is thinking of something else. Neena has heard the girl give this same speech before, maybe five hundred times before.

"My father brought me here," the girl continues, "on my sixteenth birthday."

Her head and shoulders hang off one end of the stool, her long bare legs off the other. Her legs are bent at the knees, her feet arched, only the tips of her tiny toes pressing the polished teakwood floor.

Her middle finger is buried deep inside her clipped black bush, moving slowly, in and out, in and out, as if she is hardly paying attention, or may lose interest at any moment.

Her skin is very white, as if dusted with talcum, or confectioner’s sugar, and the bones of her hips rise from an inviting pelvis that looks like a small animal designed by a primitive hunter as re-imagined by a postmodern artist.

Someone, somewhere, is methodically photographing her. You can hear the dry click and whirr like the descent of a plague of locusts.

"He was not my real father," the girl claims.

Her voice carries absolutely no emotion. She pauses a half-beat, for emphasis, but it all seems to be an afterthought. She’s not listening either, nor does she care.

"He bought me on a street in Bangkok. It was after a war."

Neena sighs, or rather acts as if she were sighing, and lays a frozen white lily to her cheek. She thinks, for some reason, of miles and miles and miles of empty green ocean and no horizon and the sound a tape recorder makes when playing back hours of nothing.

She thinks, Oh god, how meaningless, how completely and horribly unnecessary this all is….

The girl continues telling her life story, as she tells it every day.

Over and over again.

"He sold me for an indeterminate sum. I was pregnant."

The tears on her face are not real.

"I am to be ravaged," she says, quite matter-of-factly, "over a period of several days by two rats, lightly sedated, and surgically planted inside me. One will be white and the other will be black. They are clones, and yes, I know, I don't understand how that can possibly be either.”

She pauses a moment, and continues.

“It seems a little bit too derivative of Orwell’s 1984 to me. Do you think they tell me these things only to frighten me?"

Neena isn’t listening. Instead she is looking passed the girl, passed the wall, over the ocean, passed the horizon that is not there. She is listening to the tape playing nothing. She answers the girl but she feels like she is answering no one (you’re getting warmer Neena, dear) and the breath that whispers across her lips feels like the mechanically chilled air issued from an air conditioner.

"Yes,” she says, "and no."

To read the entire novel go to:

http://geishainthecityofdeath.blogspot.com

To read the entire novel go to:

http://geishainthecityofdeath.blogspot.com

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)